Jane Austen writes plot-driven masterpieces, and all her God-given skills come together in Persuasion. In Persuasion we find a twist of pathos, not present in her other novels. We can view Austen’s growth as a writer. She provides her reader the promise of a wider scope of understanding. In Scribner’s Magazine (March 1891), W. B. Shubrick Clymer says, “Persuasion does not…echo with the distant hum of the whole of human life; it is, however, a ‘mirror of bright constancy.’ Jane Austen’s observation, unusually keen always – and this is no mean qualification, for has not humor its source in observation? – here unites with the wisdom of forty to make a picture softer in tone, more delicate in modeling, more mellow, than its companions of her girlhood, or than its immediate predecessors in her later period. The book marks the beginning of a third period, beyond the entrance to which she did not live to go. It is not pretended that she would, with any length of life, have produced heroic paintings of extensive and complicated scenes, for that was not her field; it may reasonably be supposed, had she lived, her miniatures might, in succeeding years, have shown predominantly the sympathetic quality which in Persuasion begins to assert itself.”

Jane Austen writes plot-driven masterpieces, and all her God-given skills come together in Persuasion. In Persuasion we find a twist of pathos, not present in her other novels. We can view Austen’s growth as a writer. She provides her reader the promise of a wider scope of understanding. In Scribner’s Magazine (March 1891), W. B. Shubrick Clymer says, “Persuasion does not…echo with the distant hum of the whole of human life; it is, however, a ‘mirror of bright constancy.’ Jane Austen’s observation, unusually keen always – and this is no mean qualification, for has not humor its source in observation? – here unites with the wisdom of forty to make a picture softer in tone, more delicate in modeling, more mellow, than its companions of her girlhood, or than its immediate predecessors in her later period. The book marks the beginning of a third period, beyond the entrance to which she did not live to go. It is not pretended that she would, with any length of life, have produced heroic paintings of extensive and complicated scenes, for that was not her field; it may reasonably be supposed, had she lived, her miniatures might, in succeeding years, have shown predominantly the sympathetic quality which in Persuasion begins to assert itself.”

So how often do we encounter “persuasion” in Jane Austen’s last novel. But who is under the powers of persuasion?

In Chapter 1, Lady Russell speaks to Anne of the Elliots’ need to economize and asks Anne’s assistance in persuading her family to do what is necessary. Lady Russell realizes Anne is the most reasonable of the lot, and, moreover, Anne possesses skills she has learned over the years to do the impossible when it comes to her obstinate relations. “If we can persuade your father to all this,” said Lady Russell, looking over her paper, “much may be done. If he will adopt these regulations, in seven years he will be clear; and I hope we may be able to convince him and Elizabeth, that Kellynch-hall has a respectability in itself, which cannot be affected by these reductions…”

In Chapter 1, Lady Russell speaks to Anne of the Elliots’ need to economize and asks Anne’s assistance in persuading her family to do what is necessary. Lady Russell realizes Anne is the most reasonable of the lot, and, moreover, Anne possesses skills she has learned over the years to do the impossible when it comes to her obstinate relations. “If we can persuade your father to all this,” said Lady Russell, looking over her paper, “much may be done. If he will adopt these regulations, in seven years he will be clear; and I hope we may be able to convince him and Elizabeth, that Kellynch-hall has a respectability in itself, which cannot be affected by these reductions…”

In Chapter 1, Anne desires her father clear all his debts. Anne considered it Sir Walter’s duty, which demonstrates how much more mature she is to those who claim dominance over her. She wanted it to be prescribed, and felt as a duty. She rated Lady Russell’s influence highly, and as to the severe degree of self-denial, which her own conscience prompted, she believed there might be little more difficult in persuading them to a complete, than to half a formation.

In Chapter 1, when Sir Walter and his eldest daughter Elizabeth refuse to economize, the idea of their quitting Kellynch-hall to a smaller residence is suggested by Mr. Shepherd, Sir Walter’s man of business. Although Anne and Lady Russell have said the same thing, Sir Walter might be persuaded by another man. The hint was immediately taken up by Mr. Shepherd, whose interest was involved in the reality of Sir Walter’s retrenching, and who was perfectly persuaded that nothing would be done without a change of abode.

In Chapter 4, Anne reflects on why she chose to end her engagement to Captain Wentworth. She had trusted her confidante and now knows the result of such trust; yet, she does not place the blame for her misery on others. …but Lady Russell, who she had always loved and relied on could not, with such steadiness of opinion, and such tenderness of manner, be continually advising her in vain. She was persuaded to believe the engagement a wrong thing – indiscreet, improper, hardly capable of success, and not deserving it.

In Chapter 4, Anne has second thoughts about giving up Captain Wentworth, realizing she would have known happiness with him, even if they had floundered for awhile before becoming established financially. Unlike her father, she and the captain would have known how to proceed. She did not blame Lady Russell, she did not blame herself for having been guided by her; but … She was persuaded that under every disadvantage of disapprobation at home, and every anxiety attending his profession, all the probable fears, delays and disappointments, she should yet have been a happier woman in maintaining the engagement…

In Chapter 6, Anne’s family appeal to her to “tame” Mary’s tendencies for hypochondria. Again, the lesson Anne has learned is she is the steadying force in the Elliot family. It is a role she has accepted, but not necessarily one she views for herself. Known to have some influence with her sister, she was continually requested, or at least receiving hints to exert it, beyond what was practical. “I wish you could persuade Mary not be always fancying herself ill,” was Charles’s language; and, in an unhappy mood, thus spoke Mary; – “I do believe if Charles were to see me dying, he would not think there was any thing the matter with me. I am sure, Anne, if you would, you might persuade him that I really am very ill – a great deal worse than I ever own.”

In Chapter 6, Anne’s family appeal to her to “tame” Mary’s tendencies for hypochondria. Again, the lesson Anne has learned is she is the steadying force in the Elliot family. It is a role she has accepted, but not necessarily one she views for herself. Known to have some influence with her sister, she was continually requested, or at least receiving hints to exert it, beyond what was practical. “I wish you could persuade Mary not be always fancying herself ill,” was Charles’s language; and, in an unhappy mood, thus spoke Mary; – “I do believe if Charles were to see me dying, he would not think there was any thing the matter with me. I am sure, Anne, if you would, you might persuade him that I really am very ill – a great deal worse than I ever own.”

In Chapter 6, Anne takes the acquaintance of the Crofts and learns Mrs. Croft expects a brother to visit them at Kellynch-hall. Can we not all imagine the anxiousness Anne must be feeling at meeting anyone connected to Captain Wentworth? Anne was left to persuade herself, as well as she could, that the same brother must still be in question. She could not, however, reach such a degree of certainty, as not to be anxious to hear whether any thing had been said on the subject at the other house, where the Crofts had previously been calling.

In Chapter 7, Mary refuses to stay home and tend to her son when there are entertainments at the main house. Again, Anne’s family proves how self-centered they are. Could not this book also be known as “Sense and Sensibility”? “I mean to go with you, Charles, for I am of no more use at home than your are. If I were to shut myself up for ever with the child, I should not be able to persuade him to do any thing he did not life.“

Also in Chapter 7, Anne uses the excuse of little Charles’s accident to avoid meeting Captain Wentworth again. She now knows Captain Wentworth has proven as successful as he declared himself he would be. He would have succeeded. They would have succeeded. They would have known happiness, something she will likely never know. This is a hard lesson indeed. Anne was now at hand to take up her own cause, and the sincerity of her manner being soon sufficient to convince him, where conviction was at least very agreeable, he had no farther scruples as to her being left to dine alone, thought he still wanted her to join them in the evening, when the child might be at rest for the night, and kindly urged her to let him come and fetch her; but she was quite unpersuadable; and this being the case, she had ere long the pleasure of seeing them set off together in high spirits.

At the end of Chapter 7, Captain Wentworth criticizes Anne Elliot before members of her family. His pride knows no forgiveness. Wentworth is still angry with her choice. He cannot forgive her, but the reader also realizes she cannot forgive herself either. She had used him ill; deserted and disappointed him; and worse, she had shewn a feebleness of character in doing so, which his own decided, confident temper could not endure. She had given him up to oblige others. It had been the effect of over-persuasion. It had been weakness and timidity.

In Chapter 10, when the Musgrove sisters mean to go for a “long” walk in order to encounter Captain Wentworth again, Mary intrudes. How hard it must have been to view Louisa Musgrove’s pursuit of the man Anne still loves. “Oh, yes, I should like to join you very much, I am very fond of a long walk.” Anne felt persuaded, by the looks of the two girls, that it was precisely what they did not wish, and admired again the sort of necessity which the family-habits seemed to produce, of every thing being to be communicated, and every thing being to be done together, however undesired and inconvenient.

In Chapter 10, Louisa Musgrove claims “independent” thoughts before Captain Wentworth. Anne overhears their conversation of how Louisa made certain Henrietta greet their cousin/beau. Louisa is proving as manipulative as was Anne’s family. She is also naming any woman who is easily persuaded as not worthy of the captain’s attentions. Wentworth praises her independence, but within earshot of Anne. “And so, I made her go. I could not bear that she should be frightened from the visit by such nonsense. What! – would I be turned back from doing a thing that I had determined to do, and that I knew to be right, by the airs and interference of such a person? – or, of any person I may say. No, – I have no idea of being so persuaded. When I have made up my mind, I have made it. And Henrietta seemed entirely to have made up hers to call at Winthrop today…”

In Chapter 10, Louisa Musgrove claims “independent” thoughts before Captain Wentworth. Anne overhears their conversation of how Louisa made certain Henrietta greet their cousin/beau. Louisa is proving as manipulative as was Anne’s family. She is also naming any woman who is easily persuaded as not worthy of the captain’s attentions. Wentworth praises her independence, but within earshot of Anne. “And so, I made her go. I could not bear that she should be frightened from the visit by such nonsense. What! – would I be turned back from doing a thing that I had determined to do, and that I knew to be right, by the airs and interference of such a person? – or, of any person I may say. No, – I have no idea of being so persuaded. When I have made up my mind, I have made it. And Henrietta seemed entirely to have made up hers to call at Winthrop today…”

In Chapter 10, Louisa lets it slip to Captain Wentworth how her brother Charles proposed to Anne before he married Mary. He learns indirectly how Anne’s family and Lady Russell also disapproved of a man who would inherit a country estate. “I do not exactly know, for Henrietta and I were at school at the time; but I believe about a year before he married Mary. I wish she had accepted him. We should all have liked her a great deal better; and papa and mamma always think it was her great friend Lady Russell’s doing, that she did not. – They think Charles might not be learned and bookish enough to please Lady Russell, and that therefore, she persuaded Anne to refuse him.”

At the end of Chapter 10, the Crofts speak to Anne of Wentworth’s desire to marry. Mrs. Croft wants Frederick to be as happy as are she and the Admiral. Anne views a couple who came together quite quickly, but have known happiness despite the length of their initial acquaintance. This is further proof such love is possible. “We had better not talk about it, my dear,” replied Mrs. Croft pleasantly; “for if Miss Elliot were to hear how soon we came to an understanding, she would never be persuaded that we could be happy together. I had known you by character, however, long before.”

At the end of Chapter 11, Anne attempts to drag Captain Benwick from his doldrums. Above all, Anne has a kind heart, but she also knows the result of grieving for what might have been. He was evidently a young man of considerable taste in reading, though principally in poetry; and beside the persuasion of having given him at least an evening’s indulgence in the discussion of subject which his usual companions had probably no concern in, she had the hope of being of real use to him in some suggestions as to the duty and benefit of struggling against affliction, which had naturally grown out of their conversation.

In Chapter 12, Henrietta and their cousin are hoping for a curacy for Charles Hayter so they may marry sooner. Henrietta says Dr. Shirley should retire. Although not directly related to Henrietta and Charles’s relationship, this is a statement on the adamancy found in “persuasion.” “…And as to procuring a dispensation there could be no difficulty at his time of life, and with his character. My only doubt is, whether any thing could persuade him to leave his parish”

Two paragraphs later, Henrietta is still speaking. She remarks on Lady Russell’s ability to persuade another. It is a bit of irony, Austen added to the tale. “I wish Lady Russell lived at Uppercross, and were intimate with Dr. Shirley. I have always heard of Lady Russell, as a woman of the greatest influence with every body! I always look upon her as able to persuade a person to any thing!”

In Chapter 12, Wentworth advocates for Anne to stay with Louisa while either he or Charles Musgrove goes after the elder Musgroves to tend their daughter. Although Wentworth realizes Anne is the better choice, the drama of the moment causes Charles to reject the idea. Charles agreed; but declared his resolution of not going away. He would be as little incumbrance as possible to Captain and Mrs. Harville; but as to leaving his sister in such a state, he neither ought, nor would. So far it was decided; and Henrietta at first declared the same. She, however, was soon persuaded to think differently.

At the end of Chapter 12, Anne bemoans Captain Wentworth’s folly in admiring “firmness of character.” Louisa’s determination has her near death’s door and has him needing to speak his proposals if the girl survives. Wentworth’s rash behavior has proven his undoing. Anne lack of rashness proved hers years earlier. A balance was required, and they both now privately realize they could have assisted each other in such ways. Anne wondered whether it ever occurred to him now, to question the justness of his own previous opinion as to the universal felicity and advantage of firmness of character; and whether it might not strike him, that like all other qualities of the mind, it should have its proportions and limits. She thought it could scarcely escape him to feel that a persuadable temper might sometimes be as much in favour of happiness, as a very resolute character.

At the beginning of Chapter 13, Anne is at Uppercross, proving herself of use to the Musgroves. The household receives word of Louisa’s lack of recovery from Charles. Just as she has done with her own child, Mary neglects her sister-in-law, leaving Louisa’s care to a woman they barely know. In speaking of the Harvilles, he seemed unable to satisfy his own sense of their kindness, especially of Mrs. Harville’s exertions as a nurse. “She really left nothing for Mary to do.” He and Mary had been persuaded to go early to their inn last night.

Also in Chapter 13, Anne does her best to persuade Louisa’s family to go to Lyme. Anne is proving sensible again. Anne was to leave them on the morrow, an event which they all dreaded. And so much was said in this way that Anne thought she could not do better than impart among them the general inclination to which she was privy, and persuade them all to go to Lyme at once.

In Chapter 14, Anne has joined Lady Russell at the woman’s cottage upon Kellynch’s estate. They have received word from Mary of Louisa’s improvement, and although Anne does not ask of Wentworth, she learns something of him. Once again, she accepts the fact Wentworth is likely to marry Louisa. Her chance to know happiness has slipped through Anne’s fingers once more. As Louisa improved, he had improved; and he was now quite a different creature from what he had been the first week. He had not seen Louisa; and was so extremely fearful of any ill consequence to her from an interview, he did not press for it all; and, on the contrary, seemed to have a plan of going away for a week or ten days till her head were stronger. He had talked of going down to Plymouth for a week, and wanted to persuade Captain Benwick to go with him; but, as Charles maintained to the last, Captain Benwick seemed much more disposed to ride over to Kellynch.

In Chapter 18, Anne worries Wentworth and Benwick’s friendship will suffer with Benwick’s proposal to Louisa Musgrove. Despite Mary claiming otherwise, Anne believes Benwick’s character required the man to love someone. Anne feels sorry for all three involved, but she realizes Louisa’s temperament, the one Captain Wentworth so much admired, is as mercurial as he once thought hers to be. She did not mean, however, to derive much more from it to gratify her vanity, than Mary might have allowed. She was persuaded that any tolerably pleasing young woman who had listened and seemed to feel for him, would have received the same compliment. He had an affectionate heart. He must love somebody.

In Chapter 20, at the opera house, Anne hopes to speak to Captain Wentworth privately. Their earlier conversation had sparked a bit of hope in her heart. Her resolve to speak to him again even when the expression on Lady Russell’s countenance says the woman has taken note of Wentworth’s presence in the room and does not approve. The first act was over. Now she hoped for some beneficial change; and, after a period of nothing-saying amongst the party, some of them did decide on going in quest of tea. Anne was one of the few who did not choose to move. She remained in her seat, and so did Lady Russell; but she had the pleasure of getting ride of Mr. Elliot; and she did not mean, whatever she might feel on Lady Russell’s account, to shrink from conversation with Captain Wentworth, if he gave her the opportunity. She was persuaded by Lady Russell’s countenance that she seen him.

At the end of Chapter 21, Mrs. Smith explains to Anne why the woman did not speak out against Mr. Elliot sooner. Anne has come close to being persuaded by Lady Russell to marry a man with no scruples simply so Anne could remain in the family estate when Sir Walter dies. How foolish Lady Russell’s advice appears under those circumstances. Anne could just acknowledge within herself such a possibility of having been induced to marry him, as made her shudder at the idea of the misery which must have followed. It was just possible she might have been persuaded by Lady Russell! And under such a supposition, which would have been most miserable, when time had disclosed all, too late?

In Chapter 22, we learn Elizabeth’s vanity will not permit her to entertain the Musgroves, Captain Harville, the Crofts and Wentworth at their home in Bath because she does not want them to view the Elliots retrenching. Elizabeth was, for a short time, suffering a good deal. She felt Mrs. Musgrove and all her party ought to be asked to dine with them, but she could not bear to have the difference of style, the reduction of servants, which a dinner must betray, witnessed by those who had been always so inferior to the Elliots of Kellynch. It was a struggle between propriety and vanity; but vanity got the better, and then Elizabeth was happy again. These were her internal persuasions.

In Chapter 22, we learn Elizabeth’s vanity will not permit her to entertain the Musgroves, Captain Harville, the Crofts and Wentworth at their home in Bath because she does not want them to view the Elliots retrenching. Elizabeth was, for a short time, suffering a good deal. She felt Mrs. Musgrove and all her party ought to be asked to dine with them, but she could not bear to have the difference of style, the reduction of servants, which a dinner must betray, witnessed by those who had been always so inferior to the Elliots of Kellynch. It was a struggle between propriety and vanity; but vanity got the better, and then Elizabeth was happy again. These were her internal persuasions.

Later in Chapter 22, while visiting in Bath, Charles Musgrove encounters Captains Harville and Wentworth. He brings them back to the hotel to reunite with his family. Anne hopes for a renewal of the conversation she had with Wentworth at the concert hall. …Charles came back with Captains Harville and Wentworth. The appearance of the latter could nto be more than the surprise of the moment. It was impossible for her to have forgotten to feel, that this arrival of their common friends must be soon bringing them together again. Their last meeting had been most important in opening his feelings; she had derived from it a delightful conviction; but she feared from his looks, that the same unfortunate persuasion, which had hastened him away from the concert room, still governed. He did not seem to want to be near enough for conversation.

In Chapter 23, Mrs. Musgrove describes for Mrs. Croft the history of Louisa’s engagement to Captain Benwick. In many ways, Anne feels Captain Wentworth has been misused by his friend, despite the fact Benwick marrying Louisa releases Captain Wentworth from doing so. Anne felt she did not belong to the conversation, and yet, as Captain Harville seemed thoughtful and not disposed to talk, she could not avoid hearing many undesirable particulars, such as “how Mr. Musgrove and my brother Hayter had met again and again to talk it over; what my brother Hayter had said one day, and what Mr. Musgrove had proposed the next, and what occurred to my sister Hayter, and what the young people had wished, and what I said at first I never could consent to, but was afterwards persuaded to think might do very well,” and a great deal in the same style with every advantage of taste and delicacy which good Mrs. Musgrove could not, could be properly interesting only to the principals.

Toward the end of Chapter 23, Anne and Wentworth have reconciled, but as is the like, they revisit the years of separation and their recent coming together. “To see you,” cried he, “in the midst of those who could not be my well-wishers, to see your cousin close by you, conversing and smiling, and feel all the horrible eligibilities and proprieties of the match! To consider it as the certain wish of every being who could hope to influence you! Even if your own feelings were reluctant or indifferent, to consider what powerful supports would be his! Was it not enough to make the fool of me which I appeared? How could I look on without agony? Was not the every sight of the friend who sat behind you, was not thee recollection of what had been, the knowledge of her influence, the indelible, immoveable impression of what persuasion had once done – was it not all against me?”

“You should have distinguished,” replied Anne. “You should not have suspected me now; the case so different, and my age so different. If I was wrong in yielding to persuasion once, remember that it was to persuasion exerted on the side of safety, not of risk. When I yielded, I thought it was to duty; but no duty could be called in aid here. In marrying a man indifferent to me, all risk would have been incurred, and all duty violated.”

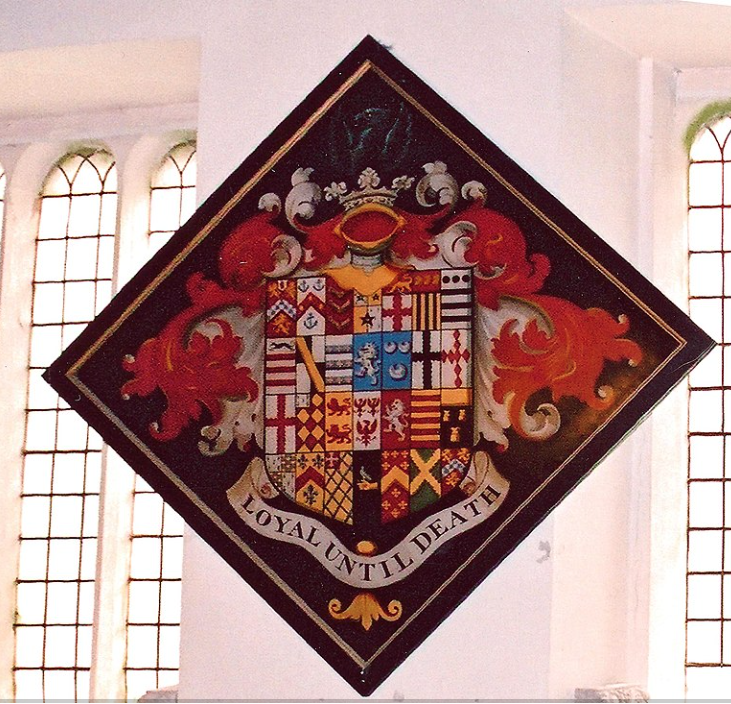

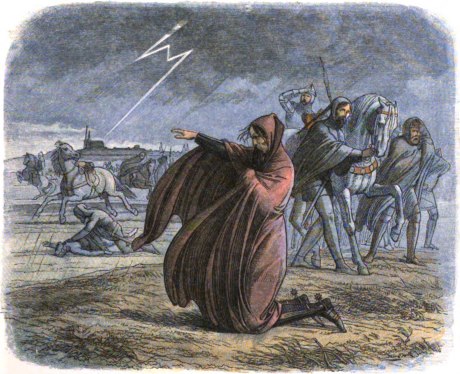

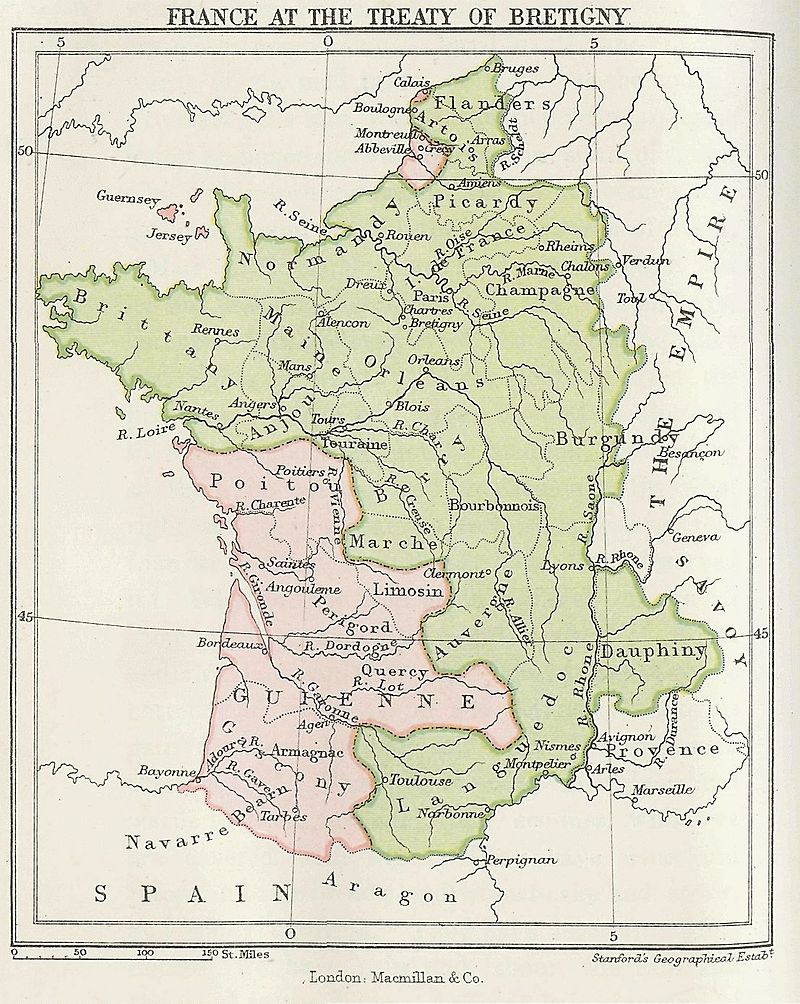

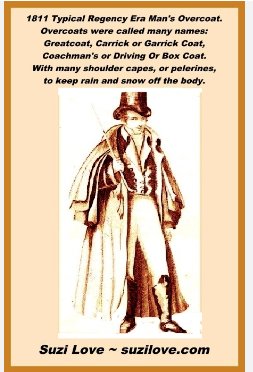

Black Monday was the Monday after Easter on 13 April 1360, during the Hundred Years’ War (1337 – 1360). The Hundred Years’ War began in 1337; by 1359, King Edward III of England was actively attempting to conquer France. In October, he took a massive force across the English Channel to Calais. The French refused to engage in direct fights and stayed behind protective walls throughout the winter, while Edward pillaged the countryside. By 13th April he had sacked and burned the suburbs of Paris and was now besieging the town of Chartres.

Black Monday was the Monday after Easter on 13 April 1360, during the Hundred Years’ War (1337 – 1360). The Hundred Years’ War began in 1337; by 1359, King Edward III of England was actively attempting to conquer France. In October, he took a massive force across the English Channel to Calais. The French refused to engage in direct fights and stayed behind protective walls throughout the winter, while Edward pillaged the countryside. By 13th April he had sacked and burned the suburbs of Paris and was now besieging the town of Chartres.

Jane Austen writes plot-driven masterpieces, and all her God-given skills come together in Persuasion. In Persuasion we find a twist of pathos, not present in her other novels. We can view Austen’s growth as a writer. She provides her reader the promise of a wider scope of understanding. In Scribner’s Magazine (March 1891), W. B. Shubrick Clymer says, “Persuasion does not…echo with the distant hum of the whole of human life; it is, however, a ‘mirror of bright constancy.’ Jane Austen’s observation, unusually keen always – and this is no mean qualification, for has not humor its source in observation? – here unites with the wisdom of forty to make a picture softer in tone, more delicate in modeling, more mellow, than its companions of her girlhood, or than its immediate predecessors in her later period. The book marks the beginning of a third period, beyond the entrance to which she did not live to go. It is not pretended that she would, with any length of life, have produced heroic paintings of extensive and complicated scenes, for that was not her field; it may reasonably be supposed, had she lived, her miniatures might, in succeeding years, have shown predominantly the sympathetic quality which in Persuasion begins to assert itself.”

Jane Austen writes plot-driven masterpieces, and all her God-given skills come together in Persuasion. In Persuasion we find a twist of pathos, not present in her other novels. We can view Austen’s growth as a writer. She provides her reader the promise of a wider scope of understanding. In Scribner’s Magazine (March 1891), W. B. Shubrick Clymer says, “Persuasion does not…echo with the distant hum of the whole of human life; it is, however, a ‘mirror of bright constancy.’ Jane Austen’s observation, unusually keen always – and this is no mean qualification, for has not humor its source in observation? – here unites with the wisdom of forty to make a picture softer in tone, more delicate in modeling, more mellow, than its companions of her girlhood, or than its immediate predecessors in her later period. The book marks the beginning of a third period, beyond the entrance to which she did not live to go. It is not pretended that she would, with any length of life, have produced heroic paintings of extensive and complicated scenes, for that was not her field; it may reasonably be supposed, had she lived, her miniatures might, in succeeding years, have shown predominantly the sympathetic quality which in Persuasion begins to assert itself.”  In Chapter 1, Lady Russell speaks to Anne of the Elliots’ need to economize and asks Anne’s assistance in persuading her family to do what is necessary. Lady Russell realizes Anne is the most reasonable of the lot, and, moreover, Anne possesses skills she has learned over the years to do the impossible when it comes to her obstinate relations.

In Chapter 1, Lady Russell speaks to Anne of the Elliots’ need to economize and asks Anne’s assistance in persuading her family to do what is necessary. Lady Russell realizes Anne is the most reasonable of the lot, and, moreover, Anne possesses skills she has learned over the years to do the impossible when it comes to her obstinate relations. In Chapter 6, Anne’s family appeal to her to “tame” Mary’s tendencies for hypochondria. Again, the lesson Anne has learned is she is the steadying force in the Elliot family. It is a role she has accepted, but not necessarily one she views for herself.

In Chapter 6, Anne’s family appeal to her to “tame” Mary’s tendencies for hypochondria. Again, the lesson Anne has learned is she is the steadying force in the Elliot family. It is a role she has accepted, but not necessarily one she views for herself.  In Chapter 10, Louisa Musgrove claims “independent” thoughts before Captain Wentworth. Anne overhears their conversation of how Louisa made certain Henrietta greet their cousin/beau. Louisa is proving as manipulative as was Anne’s family. She is also naming any woman who is easily persuaded as not worthy of the captain’s attentions. Wentworth praises her independence, but within earshot of Anne.

In Chapter 10, Louisa Musgrove claims “independent” thoughts before Captain Wentworth. Anne overhears their conversation of how Louisa made certain Henrietta greet their cousin/beau. Louisa is proving as manipulative as was Anne’s family. She is also naming any woman who is easily persuaded as not worthy of the captain’s attentions. Wentworth praises her independence, but within earshot of Anne.  In Chapter 22, we learn Elizabeth’s vanity will not permit her to entertain the Musgroves, Captain Harville, the Crofts and Wentworth at their home in Bath because she does not want them to view the Elliots retrenching.

In Chapter 22, we learn Elizabeth’s vanity will not permit her to entertain the Musgroves, Captain Harville, the Crofts and Wentworth at their home in Bath because she does not want them to view the Elliots retrenching.